ARTICLES

MADARA MANJI × 메이지 히지카타|대담 전반부

2024.07.05

INTERVIEW

Meiji Hijikata × MADARA MANJI

The series of articles delves into conversations between various artists and Meiji Hijikata, Director of the Taro Okamoto Museum of Art, Kawasaki, offering an in-depth exploration of their artworks. The sixth installment features a dialogue with MADARA MANJI, a contemporary artist renowned for his innovative use of the traditional Japanese metalworking technique "mokume-gane."

MADARA MANJI's artistic journey revolves around the intricate blending of metals to create unique patterns, symbolizing the complexity of the human spirit. His captivating works have garnered significant attention both in Japan and abroad. In this insightful conversation, the duo explores the allure of MANJI's art, discussing the meticulous process behind his creations and the profound themes he seeks to convey through his work.

Traditional Japanese Metalworking Technique "Mokume-gane"

MADARA MANJI's studio is located in a certain building in Japan, filled with materials used for solo exhibitions, samples of his work, tools, and various other items. The single-floor studio is equipped with a "fire pit" for heating and a space for metal hammering.

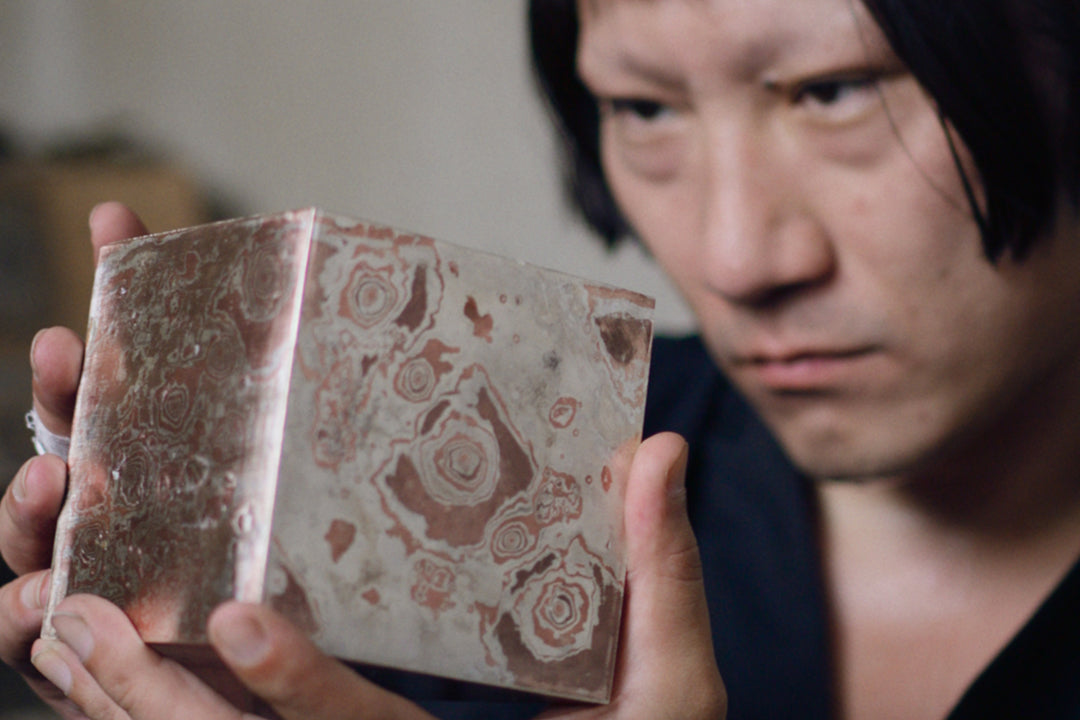

MADARA MANJI holding the materials for his work, explaining his process.

MANJI: This is the initial state of the work. It’s made by heating and combining dozens of metal plates into a single piece, which is then hammered thin. During the process, it’s shaved and polished to form unique patterns and into a large sheet.

Hijikata: Is this the traditional technique called "mokume-gane"?

MANJI: Yes, but I’ve incorporated my arrangements. Adapting mokume-gane to art with large surfaces presented unique challenges, as the technique is traditionally used for small items. Each metal's distinct properties, such as hardness and melting points, add complexity to the process. To overcome these difficulties, I made several adjustments and introduced my own arrangements, allowing me to work with mixed metals on a larger scale.

Hijikata: That makes sense since the metals are different.

MANJI: Working with metals that naturally repel each other is challenging, but I aimed to adapt mokume-gane for larger surfaces. To achieve this, I made several adjustments to overcome the inherent difficulties.

Heating the Composite Metal Piece

MANJI: The next step is to hammer the heated piece.

Hijikata: How thin do you make it?

MANJI: While bringing out the patterns, I thin this block down to about 1 mm.

Hijikata: How many types of metals are layered?

MANJI: It varies by work, but I typically use around two to four types of metals, each offering a different color. This particular piece combines pure copper, pure silver, a copper-silver alloy, and a copper-gold alloy, making it the most colorful type I've created.

Hijikata: Is that based on traditional techniques or is it original?

MANJI: It’s both traditional and original. I use "shakudo," a traditional Japanese alloy, which is rare overseas. I use various other metals as well, deciding the proportions myself and outsourcing the material production.

The piece has been hammered several times. The uneven surface is visible upon close inspection.

The Physical and Psychological Challenges of Metalwork

The multilayered non-metallic mass is heated to approximately 900°C and then subjected to an astounding tens of thousands of hammer blows. This process is extremely intense and demanding, both for the material and the artist. Why did MANJI choose such a challenging production method, which is far from easy?

Hammering the heated piece, the sharp and powerful sound reverberates through the room.

Hijikata: Do you have a particular dedication to using fire and forging—hammering—during your creation process?

MANJI: Yes, indeed. My passion for creating art began with an exploration of the theme 'What is a human being?' From both psychological and philosophical perspectives, I aimed to translate the essence of humanity into visual form.

Human beings are incredibly complex, composed of myriad conflicting elements. To convey this complexity, I initially experimented with blending different materials. However, I found that materials like clay, which naturally blend, did not align with my artistic vision. The human spirit contains elements that resist blending, generating tension and discord. This led me to select materials that inherently resist fusion.

Ultimately, I chose metal. Metal is transformed through processes of heating and hammering—energies that are inherently destructive. While this vigorous treatment can sometimes cause the metal to crack, enduring these forces results in the creation of stunning forms. This process beautifully embodies the essence of my artistic concept.

Visible concentric ring patterns and hazy mottled patterns. Various patterns emerge through heating and hammering.

Primal Creation through Human Senses

Meiji Hijikata × MADARA MANJI

Hijikata: Do you perform these tasks daily?

MANJI: The hammering is for making the initial material. Once the material is made, I move to other processes like cutting, welding, polishing, and finishing. In the overall process, hammering and shaping are about half and half.

Hijikata: How heavy is this piece?

MANJI: It’s light, about 1 kg.

The state before coloring. Using the traditional metal coloring technique called "niiro-chakushoku," the surface is intentionally oxidized (rusted) to transform into vibrant colors.

Hijikata: In your artistic process, heating and hammering symbolize a primal connection between matter and humanity, particularly with metal—a medium where altering its composition through heat evokes the creation of new life.

While the West sees parallels with alchemy, in Japan and the East, the act itself carries profound significance. Witnessing your studio practice, one feels this primal connection and your resulting works possess a compelling, persuasive power.

Your ongoing challenge lies in evolving your work further. Yet, by persistently applying heat to transform materials and shaping them through the rhythmic hammering of your senses, your art will consistently resonate deeply with viewers.

MANJI’s Work: Patterns in reddish-brown, black, and white-silver appear. In the Cube Series, the tension is heightened by cutting off one corner of the cube.

The interview took place in early June, just before the onset of the rainy season and far from the height of summer. However, as soon as MADARA MANJI began using fire, heat quickly spread throughout the room, filling the space with intense warmth. The sharp sound of hammering against the heated mass reverberated through the air.

The transformative process of heating and hammering sometimes results in a harmonious coexistence of elements, while at other times, it stirs up turbulent whirlpools of mixed, non-metallic substances.

In the latter part of the article, MADARA MANJI reflects on his journey to becoming an artist, his challenges as a contemporary artist, and his aspirations for the future.